ECONOMYNEXT – Sri Lanka’s interest rates have edged up over 2025, reducing the risk of a second sovereign default, data show, though reserve collections fell short of initial targets amid insufficient deflationary policy, analysts have said.

Sri Lanka cut rates in May 2025 amid warnings that the operating framework of the central bank was moving on well-beaten paths of ‘flexible inflation targeting’ where currency crises were triggered in the second year of International Monetary Fund programs when private credit recovered after rate cuts two years earlier triggered the program itself.

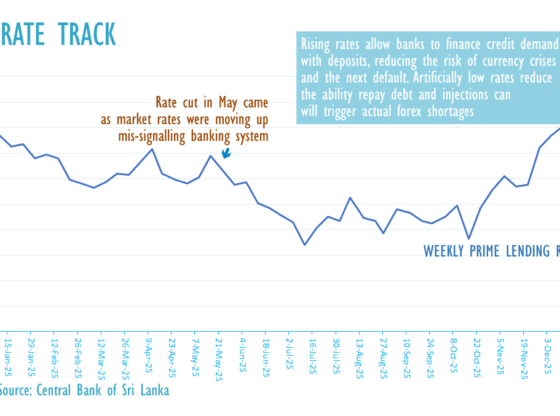

The prime lending rate, published by the central bank was 8.90 percent in the week to January 01, 2025.

The central bank cut its overnight policy rate to 7.75 percent, which has standing facilities on 50 basis points on either side, in May 22, as the Prime Lending Rate moved up to from 8.36 percent to 8.58 percent over the previous two weeks.

In the week to December 2025, the PLR had moved up to 8.94 percent.

Overnight rates have also moved up, with the maximum unbacked call money rate rising to 8.05 percent and average 8.03 percent by December 30.

The gilt-backed overnight repo rate, where trading takes place later in the day rose to as much as 8.10 percent.

Scarce Reserve Regime Improves Operating Framework

Analysts have warned that if rates remain elevated the ceiling rate has to be raised to prevent a currency crisis from open market operations and a second default.

The central bank in 2025 operated a scarce reserve regime where banks were not encouraged to give loans with central bank open market operations money, which analysts say reduces the risks of a quick currency crisis and a second default and is a major improvement in the operating framework of the central bank.

A scarce reserve regime where central bank gives money only overnight at a penalty rate, discourages banks from lending with central bank’s printed money triggering balance of payments deficits.

Interbank market activity has picked up.

Bank lending and deposit rates also edged up over 2025 based on data published by the central bank.

RELATED : Sri Lanka lending and deposit interest rates edge up amid credit demand

The ability to collect reserve declined especially after the May rate cut as private credit accelerated driving up imports.

RELATED : IMF revises down Sri Lanka reserve projections for 2025 and 2026

Analysts have pointed out that gentle rises in interest rates help prevent currency crises and depreciation as long as the central bank’s exchange rate policy is consistent.

Monetary Debasement

However, the rupee depreciated in 2025, which an analyst attributed to ‘Political Ravishment with a twist’ or selective denial of convertibility to private borrowers due to a flaw in the operating framework.

The rupee depreciation has wiped out part of the fiscal gains made by people paying higher taxes in an early warning of what could happen unless monetary stability was maintained.

RELATED : Sri Lanka govt debt grows at double the pace of budget deficit amid depreciation

Sri Lankan tax payers were forced to pay higher rates and import taxes were first hiked after the central bank ‘cut rates’ about 18 months after it was set up, triggering balance of payments trouble.

The stabilization crisis that followed ousted the first post-independent government, which set up the central bank abolishing an East Asia style currency board.

Sri Lanka was hit by Cyclone Ditwah in December, dampening economic activity. The International Monetary Fund has said the costs of growth could be around 0.2 percent of gross domestic product.

A tsunami in 2004, when the rupee was also deprecating amid money printing and private credit growth, sharply reduced credit growth in January leading to exchange rate stabilization.

In 2025, the government has announced sweeping relief payments, which can pressure credit markets, analysts say.

The funding is expected to be funded with an over-borrowed buffer, set up when the public debt was under the control of the central bank.

There have been warnings that it is not possible to build domestic buffers in the banking system for a ‘rainy day’. Such reserves have to be invested outside the country.

Large withdrawals of deposits could also stress the banks concerned, forcing them to borrow from the central banks windows, until the money comes back to other banks.

Any accommodation of the bank run style withdrawals with term liquidity operations at low rates could trigger currency pressure, analysts say.

When the central bank with money printing power (inflationary open market operations) was set up and the government could raise 20 year funds at around 3 percent.

After rate cuts capital long term interest rates are now in double digits and people are wary of buying long term debt.

“People in the streets bought 30-year Liberty Bonds in the US in the middle of a war at 3.85 percent,” says EN’s economic columnist Bellwether. “Now in peacetime after the abundant reserve regime, 10 year bonds are higher.

“The high Gross Financing Needs (GFNs) are a knee jerk reaction to volatile rates from deliberately introduced credit cycles from inflationary rate cuts.”

“The high GFN’s and the skewing debt towards the short end protects banks and also the government allowing interest costs to fall as soon as the currency crisis eases.

“The solution is not to artificially suppress bill yields in the hope of hoodwinking depositors into buying longer term bonds but to maintain monetary stability with a sound money. It is a confidence problem.”

RELATED : Sri Lanka should be careful in over-relying on GFN at the expense of stability: Bellwether

In 2025, though the budget deficit was reduced with people paying high taxes, the gains to national debt was partly wiped out with currency depreciation. Improvements to exchange rate policy in the operating framework can speed up the reduction of debt, analysts say.

Analysts have pointed out that external sovereign defaults, as seen in Latin America are not fiscal related, but are a monetary in nature which comes from intense debasement that made central banks un-accountable after the IMF’s Second Amendment to its Articles.

Sri Lanka’s inflation and interest rates were generally the same as developed nations until currency depreciation started to accelerate capital destruction in the 1980s. (Colombo/Dec31/2025)