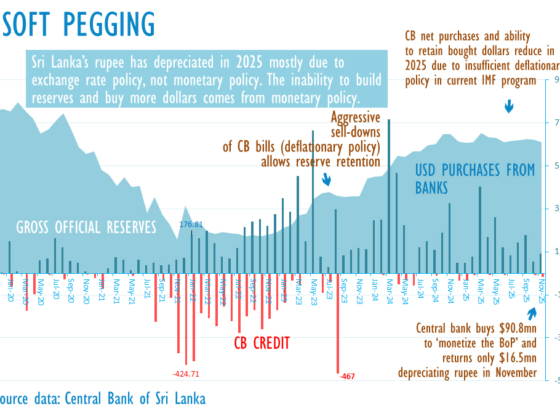

ECONOMYNEXT – Sri Lanka’s central bank has bought 90 million US dollars in November 2025 creating new money and returned only 16.5 million dollars to importers who used the money, official data shows.

The central bank bought 74.3 million US dollars on a net basis in November after collecting 45.5 million dollars in October, also depreciating the rupee.

In October the rupee fell from 302 to 304 to the US dollar and in November from 304.40 to close to 307.80 to the US dollar in the spot market as the dollar were bought.

Unlike any other party, when the central bank buys dollars it creates new money, an action which the central bank’s first Governor John Exter called the monetization of the balance of payments.

“A central bank is supremely unqualified to build reserves,” says EN’s economic columnist Bellwether. “An ordinary man on the street is able to hide 100 dollars under his mattress, forgo spending, prevent imports, and build reserves.

“The Treasury can also do that. But a central bank cannot stop imports by purchasing dollars, because it creates new money whenever it buys dollars.”

Unless the new money is extinguished, the owners of the new money (export sector workers or remittances holders and bank customers who borrow the savings) will use them for imports. Since Sri Lanka has a high private saving rate, consumption cannot put pressure on the rupee and it requires high credit growth.

If the central bank does not return the dollars, when the created rupees boomberangs on itself, as credit picks up, the rupee will depreciate.

If the central bank does not want the new money to return to its in the forex market, they have to be extinguished through the sale or central bank held securities.

In 2025 the central bank had bought 1,625 million dollars and returned only 89.3 million dollars to the public. However dollars were returned to the government (also for cash reducing excess liquidity) to repay debt while selectively denying convertibility to the people from whom dollars were bought.

RELATED : Sri Lanka’s exchange rate depreciation by ‘Political Ravishment’

There are however expectations that the rupee may stabilize in December and January if credit slows and the central bank reduces purchases, allowing the exchange rate to strengthen. Natural disasters in the past had also tended to reduce credit and consumption.

Any foreign aid that is sold in the market and not bought by the central bank can also put upward pressure on the rupee.

In 2023 and 2024, the central bank bought large volumes of dollars and retained them by selling down its Treasury bill stock.

In 2025, under the revised IMF program, the central bank was no longer required to sell down its bond stock. As a result, deflationary policy (which creates a balance of payments surplus) was limited to coupons the Treasury paid on its bond stock.

The claim made by macro-economists that the rupee is ‘market determined’ is not correct because there is an active exchange rate policy when dollars are purchased to build reserves and also to give to the government.

Exchange rates are determined purely by monetary policy (domestic anchor like an inflation target) in a clean float and purely by exchange rate policy in a hard peg and a hotchpotch of unpredictable monetary and exchange rate policies in a flexible or discretionary exchange rate regime.

When the anchors conflict, there is depreciation and price rises.

President Anura Dissanayake in his budget speech urged that the exchange rate be kept strong.

When currencies depreciate and energy prices go up, imported and exported food prices go up, the CEB and SriLankan Airlines make losses, the public holds politicians accountable.

When currency starts to depreciate, there is also a confidence shock, with importers covering early, and exporters delaying conversions.

Analysts had warned that the central bank would not be able to collect more reserves unless its bond stock was sold down.

In addition, the central bank also cut rates in May, amid warning that the rate cut was out of line with domestic credit developments, driving up credit and investment imports.

In December Sri Lanka made a request for another International Monetary Fund loan, dashing hopes that the current IMF program will be the last.

The IMF loan has the hallmarks of the post civil war practice of trying to borrow out of the rate cuts, Bellwether says. (Colombo/Dec19/2025)